Tip Sheet

Connecting with Families in Black and Indigenous Communities

Download This Resource

A Network Monthly Resource: May 2023

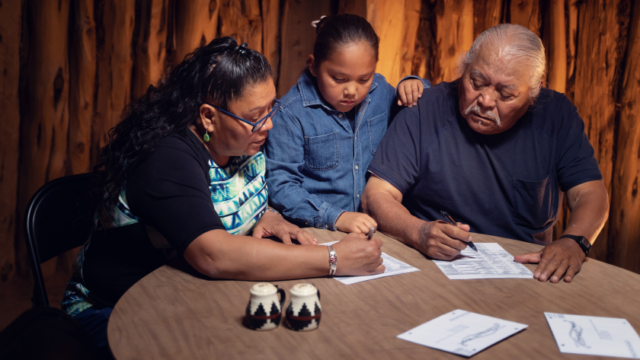

Kin/grandfamily caregivers’ ideas about their roles in protecting and providing for the children in their care depend on their families’ values and cultures.

Working with Black and Indigenous families requires knowledge of culture and context. Some questions to think about:

What are the family’s expectations concerning the care of children?

Two-generation nuclear families are not always the norm. Anita Thomas, Ph.D., talks about the supervision and support in Black families that is provided by fictive (non-blood) kin. This sense of collective responsibility is also felt in tribal/Indigenous communities. Generations United GRAND Voice Rosalie Tallbull, describing her early life, says, “The entire [Northern Cheyenne] tribe resided as one family. Everyone shared the upbringing of children. One thing that I remember very vividly—aunts and uncles had the authority to correct any wrongdoing.”

Is it culturally acceptable to discuss problems outside the family?

That depends on the family. Some families may rely on other family members, church or other spiritual leaders, and elders in the community to resolve family matters. Intervention by outsiders, including providers of mental health services, may not always be welcome. Extended family may not be considered outsiders and can be helpful.

Are social services agencies considered trustworthy?

Mistrust exists toward service agencies for many reasons. The legacy of slavery has led Black families to a mindset Dr. Thomas describes as “protective paranoia,” a guardedness in dealings with those who can remove children from their household. The history of Indian boarding schools and other government abuses have created a similar wariness in Native communities. These concerns remain well-founded, as data shows that, due to a combination of discriminatory government policies and cultural strengths of caring for each other, Black children and Native children are overrepresented in kinship/grandfamilies.

How can you make policies and practices more inclusive?

Anita Rogers, Ph.D., offers these recommendations:

- Review your intake forms with advisors from the communities and cultures you serve. Revise using a strengths-based approach.

- If a parent is not currently involved in their child’s day-to-day care, avoid making assumptions about the parent’s love or commitment.

- Ask about the family’s goals and current caregiving practices. What would they like support with or information about? Culture shapes childrearing practices and goals, so it’s important to listen and learn before making recommendations.

- Think about how your organization describes the services you’re offering. “Conversation circle” may be more inviting than “support group.”

- Ask about days and times that work best for families. When planning group gatherings, ask group members or advisors what types of foods they prefer.

- Ask how family members would like to be addressed. Some families may prefer being addressed with more formal titles, like Mr., Mrs., or Ms.

- Identify community partners, like clergy and/or elders, who can support the delivery of culturally competent services and help to bridge cultural gaps.

See these resources on Black and Indigenous communities for more information on providing culturally competent services to these children and families.